Melanoma In Dogs

Brindle, black, white, red or something entirely different — if you just love your dog’s fur color, you can thank his or her melanocytes. These are the pigment cells present in our bodies as well as in dogs. They help determine not only fur color but also whether a dog’s skin is black or pink. Despite their role in making your dog adorable, even these cells can be a source of cancer.

Cancer that originates from the melanocytes is called melanoma. Since melanoma in humans is considered one of the deadliest types of skin cancer, that might cause some alarm. However, canine melanoma is significantly different in many ways, including the fact that about 90% of typical melanomas on a dog’s skin are benign (non-cancerous). Dogs can also get oral melanoma and digital melanoma (tumors on or between the toes) that are more serious. In rare cases, a melanoma can even form around the anus. There are treatment options for all types.

Any breed of dog can develop melanoma. While a dog’s sex is not a factor, age is, as most dogs with melanoma are 9 years of age or older. It’s worth noting while exposure to the sun’s ultraviolet rays is considered a risk for melanoma in humans, it’s not considered a big risk factor of melanoma in dogs.

How To Make An Appointment

Reach out to us at (833) 467-2836, or streamline your request by selecting one of the options below:

Types and Symptoms of Melanoma in Dogs

Signs that a dog might have melanoma differ depending on the type:

Skin (dermal or cutaneous) melanoma: A skin melanoma can present in obvious or subtle ways, so check your dog carefully if you are concerned about him or her having melanoma. Tumors are often pigmented or black but not always — those are called amelanotic melanomas. Sometimes they are masses than can be felt but they also can be flat lesions on the top of the skin.

Oral melanoma: Any mass discovered in a dog’s mouth should be checked out by a veterinarian. A melanoma is often pigmented or black and can be raised or flat. However, our canine friends can develop an amelanotic melanoma in the oral cavity which would not be pigmented but instead be flesh (or gum) colored. A dog with an oral melanoma also may have halitosis (bad breath) and may drool or even have bloody or ropey saliva. Discomfort also could prompt a dog to cock his or her head to one side, have difficulty eating, or shy away if you reach to pet him or her.

Digital tumor: A melanoma tumor between a dog’s toes or affecting the toenail might be more difficult to spot until it grows big enough to be obvious. However, it might reveal itself through signs such as a loose toenail or one that is shaped or growing irregularly. The dog could be lame or limp on the affected area, and also the toe might bleed or look infected. At times, the first clinical sign will be that your dog is licking this paw incessantly, so it would be important to have this area evaluated.

Any of these melanomas can metastasize (spread), as well. Malignant melanoma typically will spread to the lungs or regional lymph nodes. Less commonly, it can spread to the liver and other organs, including the brain. One of the symptoms that canine melanoma has spread is weight loss occurring even when the dog has a good appetite. He or she also may act lethargic.

Diagnosing Melanoma in Dogs

If your pet is exhibiting any of the symptoms of melanoma in dogs, a visit to your veterinarian is in order. To try to pinpoint the cause and the extent of progression, a veterinarian typically will start with bloodwork, to get a complete blood count (CBC) and blood chemistry profile. Along with a urinalysis, these can help determine whether there are any kidney/liver/electrolyte abnormalities just to name a few. Imaging procedures to determine spread or get a visual of a tumor may include 3-view chest X-rays, CT scan, and/or an abdominal ultrasound. Your veterinarian might also take X-rays of the jaw if this is an oral mass or X-rays on the paw if a digital tumor is suspected. If there’s reason to believe metastasis has occurred, the veterinarian may aspirate the liver. It is often a good idea to aspirate the draining lymph nodes in the area or any lymph node that is enlarged to assess for spread. This involves using a fine needle to collect a tissue sample, which then typically is sent to a lab for further analysis by a veterinary pathologist. For the actual mass, your veterinarian might also do a fine needle aspirate (aspiration cytology) or might suggest doing a tissue biopsy to obtain a definitive diagnosis.

Before finalizing a diagnosis, a veterinarian typically will rule out other possibilities. For instance, while a melanoma is the most common oral tumor, other types of cancer must still be ruled out. Similarly, for a tumor between the toenails, a veterinarian will make sure that it isn’t an infection causing the issue or that the mass isn’t a sarcoma or mast cell tumor.

Treating Canine Melanoma

There are numerous treatment options available to help dogs that have melanoma. It can even be cured in some circumstances. The best treatments for each vary based on what type of melanoma is diagnosed.

Melanoma on the skin: About 90% of such melanomas are benign and, hence, don’t spread. Surgery to remove the melanoma can be curative if clean, wide margins are achieved, which means that the outer and the deep edges of the removed portion show no sign of melanoma cells. For dogs that have a malignant form of this disease, consult with a veterinary oncologist is recommended to discuss the melanoma vaccine, radiation therapy or chemotherapy.

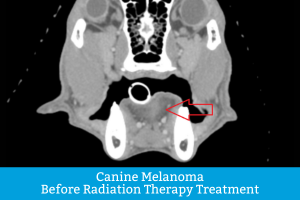

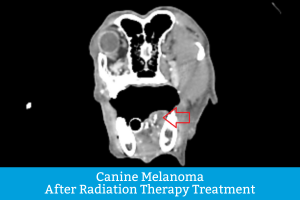

Digital melanoma: The go-to treatment is amputation of the affected digit (toe). In general, dogs do well with one digit amputated, as long as the cancer has not spread. There’s a good chance cancer won’t return for possibly a year, though there are factors (such as mitotic rate, etc.) that could alter the prognosis. If clean margins are not obtained or if amputation is not a viable option, then radiation therapy might be recommended. There are two primary types of radiation: conventionally fractionated radiation therapy (CFRT) and stereotactic radiation (SRS). Both target the tumor with high-energy particles in hopes of either killing the tumor or slowing its growth. SRS is the more innovative option, as it uses higher doses of radiation and precision targeting, thereby protecting the surrounding tissues better than CFRT. Notably, it also typically requires fewer treatments (1 to 3, vs. 15 to 21 with CFRT) and thus significantly decreases the number of times a dog must be anesthetized. There are veterinarians who specialize in radiation oncology. Additional options might include chemotherapy or a melanoma vaccine in the hopes of prolonging the disease-free interval, as this tumor frequently recurs. You may want to consult with a veterinary oncologist.

Oral melanoma: The treatment of choice for an oral melanoma is to remove the mass. That may include removal of part of the mandible (lower jawbone) or maxilla (upper jawbone). These procedures, hopefully, would be only a partial maxillectomy or mandibulectomy. The goal is to debulk the mass (remove as much of it as possible). Some cancer cells could be left behind. Unfortunately, this cancer tends to come back. Alternatively, radiation therapy (discussed above) may be an option to save the jawbone. Consult with a veterinary oncologist is recommended to further discuss the melanoma vaccine and chemotherapy.

The aforementioned melanoma vaccine is often a viable option for oral melanoma, too. It stimulates the body to make antibodies that fight the melanoma cancer cells. Side effects could include a low-grade fever, lethargy or inflammation at the injection site, but those are not exhibited in the majority of cases. The regimen typically calls for getting a vaccination once every two weeks for four treatments then a booster vaccination every six months thereafter. It is imperative to note that this vaccine was developed and meant for dogs that have local tumor control. This means that the mass was already surgically excised or treated with radiation therapy. For some oral melanomas with local control and the vaccination, there is a 70% chance of slowing down the cancer or achieving remission, on average, for a little over of year. However, some dogs go on to be cancer-free for longer than that. Noteworthy is that it may take a dog’s body four or five months to mount an adequate immune response, so the patient must have time on his or her side. If the veterinary oncologist is concerned about the four- to five-month vaccine timetable, chemotherapy (typically intravenous for oral melanomas) may be recommended. A few studies have shown some benefit to chemo.

Anal/rectal melanoma: As a reminder, these tumors are very, very rare. If an anal or rectal melanoma is diagnosed, excision is preferred. The effectiveness of the melanoma vaccine for anal/rectal melanomas is unknown, but its consideration as an option and is worth a conversation with the veterinary oncologist.

Forgoing treatment: If malignant melanoma in dogs is left untreated, the tumor(s) will continue to grow. In the case of an oral mass, some dogs will stop eating and their quality of life will decline. With digital melanoma, the affected paw can become sore and/or uncomfortable. The mass can also grow up the leg. Pain medications and antibiotics may be of some comfort. Other clinical signs of progression include weight loss and lethargy. Always leading with your pet’s best quality of life in mind, you may face a decision about euthanasia sooner or later.

PetCure Oncology Treats Melanoma in Dogs

At PetCure Oncology, we offer a wide range of options for treating melanoma and other types of cancer. We specialize in SRS radiation therapy — and our expertise and experience are matched by our compassion. We truly care for all of our patients and our mission is to provide your pet with the best quality of life possible while extending your time together. For more information about our treatment options, find a location near you and contact us today.

The contents of this article were provided in part by Dr. Renee Alsarraf, DVM, DACVIM (Oncology), a board-certified veterinary medical oncologist and member of PetCure Radiation Oncology Specialists (PROS).

If your dog is displaying any symptoms of cancer or has been diagnosed with cancer, sort below by cancer type or tumor location to learn more about the most common types of cancer in dogs and available treatment options. Click on the links for more specific information on treatment and real patient stories.

HEAD & NECK TUMORS IN DOGS

PELVIC CANAL TUMORS IN DOGS

- Anal Gland Adenocarcinomas in Dogs

- Transmissible Venereal Tumors (TVT) in Dogs

- Prostatic Tumors in Dogs

OTHER TUMORS IN DOGS

CARCINOMA/EPITHELIAL CANCER IN DOGS

- Adrenal Tumors in Dogs

- Anal Gland Tumors in Dogs

- Basal Cell Tumors in Dogs

- Biliary Cancer in Dogs

- Bladder, Prostate & Urethra (Transitional Cell) Cancer in Dogs

- Chemodectomas in Dogs

- Ear (Ceruminous Gland) Cancer in Dogs

- Liver (Hepatocellular) Cancer in Dogs

- Lung (Bronchogenic/Non-Small Cell) Cancer in Dogs

- Nasal (Sinonasal/Paranasal) Cancer in Dogs

- Neuroendocrine Carcinoma in Dogs

- Pancreatic Cancer in Dogs

- Perianal Cancer in Dogs

- Prostate (Prostatic) Cancer in Dogs

- Kidney (Renal) Cancer in Dogs

- Salivary Gland Tumors in Dogs

- Squamous Cell Carcinomas in Dogs

- Thymoma Cancer in Dogs

- Thyroid Cancer in Dogs

- Tonsillar Cancer in Dogs

ROUND CELL CANCER IN DOGS

SARCOMA/MESENCHYMAL CANCER IN DOGS

- Astrocytoma Cancer in Dogs

- Bone (Osteosarcoma) Cancer in Dogs

- Brain (Glioma) Cancer in Dogs

- Brain (Meningioma) Cancer in Dogs

- Chondrosarcoma Cancer in Dogs

- Choroid Plexus Papilloma in Dogs

- Ependymoma Cancer in Dogs

- Fibrosarcoma in Dogs

- Hemangiopericytoma in Dogs

- Histiocytic Sarcoma in Dogs

- Peripheral Nerve Sheath (Schwannoma) Tumors in Dogs

- Multilobular Osteochondroma in Dogs

- Oligodendroglioma in Dogs